At a time when France is preparing to unveil yet another plan to uproot vines, drug use—especially cannabis consumption—has reached unprecedented highs. This is the paradoxical conclusion reached by essayist Jérôme Fourquet in one of his latest media appearances. For many years, Fourquet has been examining the shortcomings and changes in French society with rare relevance. In the space of a few years, relaxation and carefree behaviour have gone from wine… to drugs. Is there still time to save wine?

Wine consumption is plummeting among young people. For a long time now, they have been turning away from it in favour of all sorts of ignobly sweetened and flavoured strong alcohols. And then the so-called ‘recreational’ use of cannabis took over.

Whose fault is that? The public is constantly repeating the same refrain: alcohol is bad, especially for young people, more and more of whom are regularly experiencing serious drunkenness at an increasingly early age or turning to so-called ‘soft’ drugs.

The figures speak for themselves. One in four deaths among 20-39-year-olds is due to alcohol. Around half of 18-34-year-olds have experienced a ‘binge drinking’ episode in the last 12 months, and 13.4% of 18-24-year-olds get drunk more than ten times a year—compared with just 1% of over-55s.

These figures reveal the dangers of a policy that has been applied progressively and methodically for so many years, aimed at stigmatising ‘alcohol’ consumption and banishing it from household habits, without any discernment as to which products are pilloried, leaving young people alone to face the worst products without having developed responsible drinking habits.

In this field of ruins, the advocates of decriminalising cannabis are making their voices heard. Their simplistic argument can be summed up as follows: for centuries, we have tolerated the consumption of alcohol, which is a psychoactive substance that can cause physical and psychological damage and dependence, so why not authorise cannabis? If we ban cannabis because it’s harmful, let’s ban alcohol, they argue, using a fortiori reasoning. The argument is extremely poor. As whistleblower Marc Vanguard reminds us on X, “we’re not going to ban alcohol because it’s a mass cultural practice that has always been legal on our soil. That’s not the case with cannabis. Maintaining a ban is not the same thing as going back on a right that is older than France itself. Especially when it’s a practice shared by 85% of French people (compared with 10% for cannabis).”

Above all, we need to know what we mean by ‘alcohol.’ Unfortunately, no causal link is ever established between the fact that the young people who go into alcoholic comas or damage themselves with joints are the same ones who don’t drink wine. It is significant that young people, backed up by communication campaigns from the road safety authorities and the Ministry of Health, talk about drinking alcohol, not wine, reducing the tasting experience to that of a degree expressed as a percentage, as written on pharmacy bottles. We can only defend the legitimacy of ‘alcohol’ as opposed to cannabis by pointing out that the term covers very different realities, and that we need to distinguish between the harmful effects of alcohol and the beneficial effects of wine—which is now depreciated and underestimated.

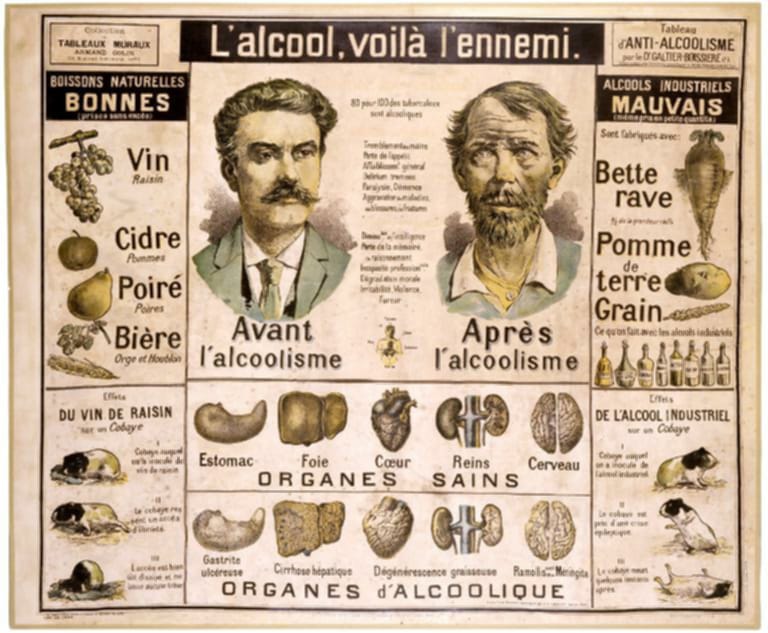

Yet our forefathers had the wisdom to know the difference. Posters hung in classrooms during the Third Republic distinguished between fermented beverages as old as the history of mankind—or almost—such as wine, beer, or cider, and distilled spirits, which were ‘recently’ produced and clearly worse for your health.

Young people no longer drink wine simply because they’ve never been taught to drink it. Wine, and especially French wine as it has developed over centuries of culture and gastronomy in our country, is a beverage that can only be enjoyed under certain conditions. It is to be accompanied by nourishing food, in a beneficial and essential exchange: digestion is facilitated by the absorption of wine, which itself reveals all the aromas of this food. Think of the magnificent marriage of red wine and Camembert cheese. Wine is enjoyed and shared in social and communicative settings: the family table, dinners with friends, the café counter. It is the perfect accompaniment to discussions and conversations. Drinking it in moderation relaxes the mind, and communicating with others and controlling the gathering helps to regulate its intake.

Wine is the drink par excellence for taming alcohol. Expelled from everyday life with the help of health and hygiene precautions, it has disappeared from the mainstream. At the same time, and more generally, the consumption of alcohol has also disappeared from everyday life, ending up being associated first with the exceptional, then with transgression and prohibition. The proof a contrario is that the categories of the population that drink the most wine regularly are also those that experience the least chronic drunkenness. Numerous statistics also prove that in Europe, the death rate from alcoholism is inversely proportional to per capita wine consumption. Young people have not learned that alcohol, in the form of wine, is a simple thing to regulate, as long as it is shared in a setting that encourages discussion and the intake of food that enhances its effects.

Behind wine, an entire cultural heritage specific to France is being depreciated. Let’s face it, wine has become politically incorrect. It conveys an image of France as obscurantist and outdated, indissoluble in a globalised world. Patriarchal, dare we say it.

The collateral damage of its ostracism is numerous: first and foremost in terms of cuisine. The fall in wine consumption is accompanied by the same collapse in the regular consumption of traditional dishes. In Parisian bistros, bourguignon and blanquette have been largely great-replaced by burgers and vegetable woks. For young people, wine is ‘beaujolpif’, the big red that stains (le gros rouge qui tache), while cocktails and spirits conjure up dreams of a trendy colourful Californian world. Sausage and terrine stink and are not ‘healthy’.

Unsurprisingly, red wine has seen the biggest drop in consumption. Wine and charcuterie are thought to be responsible for cardiovascular disease, while fast food and ready-made meals, which are far more harmful because of their excessive use of ultra-processed fats and sugars, are absolved. Information campaigns on the harmfulness of these foods, coupled with the consumption of soft drinks, go unheeded. Then it’s too late to pick up the pieces and remind people that the family table, with its fixed mealtimes and traditional dishes, is still the best remedy we have found against obesity.

Today, consumption patterns have changed.

Wine has become an alcohol like any other. People are wary of it, savouring it in small bursts, occasionally pretending to be connoisseurs, looking for environmental labels. Wine dares to show itself timidly in advertising, at Christmas or New Year’s Eve, with visuals so psychedelic and conceptual that the product ends up disappearing beneath the marketing. It’s all become terribly intellectual.

Confining wine to an amateur pastime means sacrificing cuisine. In itself, it’s never just about meat with or without sauce. But traditional cooking is also accompanied by an education in prudence, temperance, and self-control. It’s about festivities and entertainment. A taste for sociability, a capacity for negotiation… and, ultimately, a certain political responsiveness and a passion for discussion that has been the hallmark of French democracy. Obesity is highest in those countries where people spend the least time at the table, but who today, politically, would enjoy defending the traditional French meal through a public health policy?

Let us be optimistic. Although wine has lost its status as a cultural exception, all is not lost. After years of decline, since 2015, wine has once again become the favourite drink of the French, neck and neck with beer. France continues to promote the tourist appeal of its vineyard landscapes, from Alsace to Anjou.

But we have to fight, because the law continues to ban any communication on the virtues of regular, moderate consumption of wine. What a pity, when there have never been so many good wines, and public health could do with the “healthiest and most hygienic of drinks,” in the words of the great Louis Pasteur.

The fight against alcoholism and its corollary, the fight for road safety, are leading governments down the slippery slope towards a public health reform modelled on that of the United States—a country that cannot really be said to have a model population in terms of public and private health-focused social policy.

Rumour has it that the European Union is working on new legislation on alcohol consumption, inspired by the practices already in place for tobacco or by bringing together the ingredients of a new form of counterproductive prohibition.

Wouldn’t it be a good idea, before any unhealable wounds are inflicted on the next generation, to promote a responsible policy on wine consumption, especially in France, a country that has cultivated its excellence for so long? This policy, like any heritage policy, if we consider that wine is one of the constituent elements of French heritage, cannot be limited to a policy of classification—the expansion of the A.O.C. (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) is probably to wine what inclusion in the inventory and catalogue of historic monuments is to buildings; guaranteeing a certain quality, it ends up making wine something beautiful and worthy of admiration, but dead. It is through education and the transmission of wine-drinking skills that the future of wine can be guaranteed. An education in wine designed as an apprenticeship in living in society, and a taming of the excesses of alcohol. Wine education that would be permitted, but not entirely managed, by the state. There could be a number of ways to achieve this: an end to the perpetual stigmatisation of wine in public campaigns in favour of moderate drinking, with a clear distinction between strong spirits and wines; greater flexibility in advertising; and, why not, an introduction to wine tasting in schools from secondary school onwards, as part of biology lessons, for example. We can always dream. The advocates of education by example and empowerment, of the refusal of authoritarian prohibition, could have a field day here. In Vino Veritas, the truth is in the wine—remember that this adage was shared by Rabelais and Pasteur alike.